Why we’re not scanning in with the COVID tracker app (or why we don’t do what we intend to)

An ongoing challenge in New Zealand’s battle with COVID-19 has been people’s compliance with seemingly simple behaviours such as mask wearing in public spaces during lockdown, and use of the COVID tracer app. While these simple behaviours can reduce the spread of future outbreaks, and the likelihood of future lockdowns, clearly there is a barrier stopping people.

Ultimately these barriers are psychological in nature, reflecting well-documented decision-making biases. And this means we need to look to understand the drivers of these behaviours, to develop effective solutions.

It’s not a challenge of intention … it’s a challenge of behaviour

Research from The 2020 Vision Project has pointed to people’s willingness to do ‘the right thing’. When talking to some of our participants we found people were generally supportive of steps such as wearing masks in public spaces such as public transport and supermarkets, and scanning in with the COIVD tracer app. One person said: “I really don’t mind wearing them … it’s not that hard to wear a mask for 20 minutes while you run into the supermarket”.

This matches recent survey results from Dynata (collected December 2020), showing that people understood the gravity of the situation, finding that 79% believed that NZ needed to avoid taking unnecessary risks in relation to COVID-19. Data collected by Dynata in August 2020, shows a similar story, with more than 60% supporting the idea of wearing masks in public spaces such as supermarkets during Level 2.

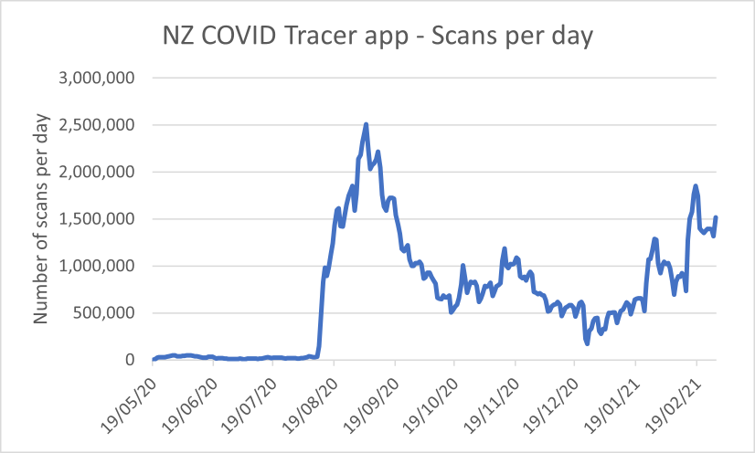

But clearly that’s not the full story. After each community outbreak, we see spikes in COVID app usage – which drops again soon after. This is despite frequent requests from the likes of Ashley Bloomfield to continue using the app when out in public to control future outbreaks: "We all have a responsibility to support contact tracing by keeping a record of our movements, either with the app or by another method such as a diary”.

Figure 1: Number of daily scans and diary entries using the NZ COVID Trace app. Source: NZ Ministry of Health

Is it that people can’t be bothered? Or is there something more?

In our conversations with people, it became clear that the intention was there – people knew how they should behave and wanted to do it. But as time wears on, day-to-day issues become more urgent and salient in people’s minds. This results in decreased motivation to follow through with the behaviour, at the time the behaviour needs to be enacted.

As one person said: “I feel bad about [not scanning in] and I should do it … the other day I was looking at something on my phone and I walked straight past [the QR code]”

Why does this happen?

This challenge – getting people to follow through with how they know they should behave – is something very common. This affects everything from our attitudes towards sustainability (do we use the single-use plastic bag in the produce department even though we know it carries a long-term cost?), and our willingness to save for retirement, amongst other things.

It can come down to several reasons – and all might be acting to influence people’s behaviour. An effective behaviour change strategy requires robust insights into what these reasons might be.

For example, in the case of using the COVID tracer app, we know that small inconveniences (or friction) can have a large impact on what people do. This is why Amazon’s one-click ordering has proven so successful – they’ve taken away one point of friction to people doing what they wanted to do.

Another factor could be the reduced risk saliency in people’s minds – over time, information is downgraded in people’s minds until a new incident increases its space in our consciousness. As an example, whenever a well-documented plane crash occurs, anxiety about flying increases – despite the car ride to the airport being more dangerous.

Finally, we could also be seeing something called temporal discounting, in which costs incurred today, even trivial costs such as opening an app, are seen to outweigh the benefits incurred in the future. In one famous case study, Bank of America was able to reverse this impact, by allowing retirement fund customers to upload a picture of themselves and see how they would look in the future – making our future self (and the benefits it will experience) more readily apparent to our current self).

What do we do now?

Many of the challenge’s organisations are facing, whether from COVID-19 or more everyday customer challenges, are psychological in nature. Understanding what is impacting your customer’s decision – even when it doesn’t make sense at first glance – is the first step to developing an effective strategy.

If you’d like to find out more about how to understand the psychological drivers impacting your organisation’s users, feel free to get in touch with Cole Armstrong at NeuroSpot (cole@neurospot.co.nz) or Mark Finnegan at Clarity Insight (mark@clarityinsight.co.nz).