The Peak-End – What drives customers' memory of an experience?

What moments will have the greatest impact on your customer?

I want you to remember the last time you had a great experience. Maybe it was a great meal at a restaurant, or a flight on an airline. Now think of the last time you had a bad experience – maybe it was an online order that went missing or being charged for the mini bar in your hotel that you definitely didn’t touch.

What do you remember? Whether good or bad, what springs to mind isn’t the whole experience but snippets of that experience.

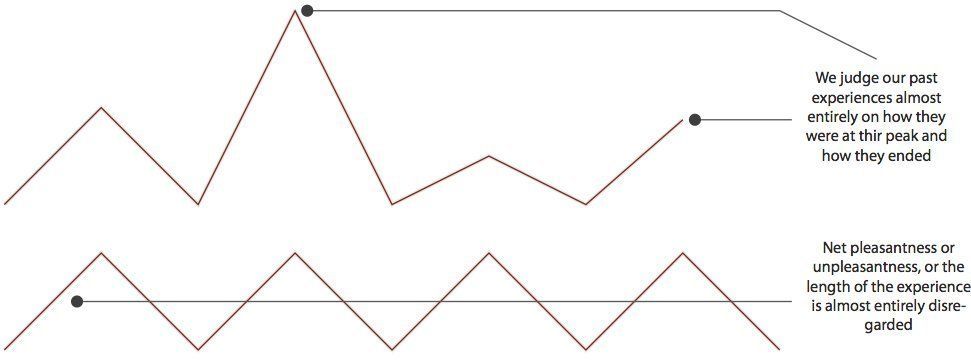

Our memory of life’s events isn’t a movie reel or a complete catalogue of what we’ve been through, but rather a highlight reel of key moments. And we are hardwired to focus on key moments of an experience; we’re programmed to heavily weight the most emotionally intensive moments of an experience, and the final moments of an experience. This forms the basis of our memory of an experience, and is known as the Peak-End rule.

What’s the implication for customer experience? Well it’s not the experience itself that influences our future behaviour and likelihood to re-engage with a brand, but our memory of the experience. And by understanding which moments matter most to that memory we can make massive strides in improving our customer’s remembered experience by focusing our efforts for greater impact.

The Peak-End rule

The Peak-End rule comes from work by Daniel Kahneman, who won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics, and his colleague Donald Redelmeier. In a series of very uncomfortable studies involving people putting their hands in ice buckets or studies with colonoscopy patients having cameras inserted inside their rectum, they were able to demonstrate that:

“The peak-end rule is a psychological heuristic in which people judge an experience largely based on how they felt at its peak (i.e. its most intense point) and at its end, rather than based on the total sum or average of every moment of the experience.”

For example, in Kahneman & Redelmeier’s 1996 study 154 colonoscopy patients were asked to rate their levels of discomfort at 60 sec intervals throughout the procedure, and then asked to retrospectively describe how uncomfortable the procedure was after it had finished. What they found was that the average level of discomfort had no correlation with how uncomfortable they reported the procedure retrospectively. What was relevant was the level of discomfort in the final moments of the procedure, and the highest (peak) level of discomfort.

In an interesting follow-up, and one with implications for customer experience, Kahneman & Redelmeier did something unusual. They divided a group of colonoscopy patients into two different conditions: one group went through the standard procedure where the camera was immediately removed after an extremely painful procedure, but the second group had the camera remain inside them for an extra three minutes in an uncomfortable but not painful position. The second group, whose experience lasted longer in reality but had less discomfort at the end, evaluated the procedure as being less painful and were more likely to return for subsequent procedures.

What does this mean? People don’t evaluate an experience based on some average measure of satisfaction/ happiness/ discomfort. What drives their memory of an experience is the peak levels of emotional intensity (whether good or bad) and how they felt at the end of an experience. And this can be influenced by carefully engineering the experience.

Engineering great peak and end moments

Brands are in a race to build better and better experiences for customers mapping out journeys in a desire to build brand advocates and ensure they’re not pushing away potential customers. And long may it continue.

But not all moments are created equal, and some brands are more aware of this than others.

AT&T for example has identified two peak moments that they focus on when customers visit their store – the initial entry to the store, and when they are waiting to speak to someone. And if they miss these moments they know it has a dramatic impact on customer satisfaction – “not gradually but off the cliff” according to AT&T’s President of Retail Sales and Service, Paul Roth. So, their expectation is that a member of staff will greet all customers within 10 feet and 10 seconds of entering the store, and customers names are placed on a list to be served, giving reassurance that they will be seen to in a fair order.

For a local example, Air New Zealand’s coffee app in the Koru lounge is often mentioned as an example of great customer experience design. By carefully understanding the customer journey, where there was an opportunity to create an emotional high point, they’ve been able to engineer a moment that has disproportionally affected people’s perception of their journey (a flat white vs 14-hour flight to LA?). While getting everything else in the journey is undoubtably important – it’s this one simple emotional trigger that is being recalled by travelers.

You could also argue that a rock concert is a similar example of a “brand” demonstrating the Peak-End rule. Whether it’s U2, The Foo Fighters or some other big arena band, your memory typically relates to the one or two key songs (peak moments) and the mandatory encore (end moment), building an exceptional memory of getting it right.

So, what’s next? Focus your attention of what matters

There’s a clear implication from this rule. Rather than spreading your resources too thin, trying to deliver a uniformly good experience, try creating a smaller number of moments of great experience. Look for an opportunity with your brand, one thing you can engineer (preferably at the end of the experience) to create a moment of delight for a customer.

Best thing, these moments don’t always have to be expensive or resource heavy, as demonstrated by my local café and the design they left on the top of my flat white. It just takes commitment to delivering a moment of splendor at key moments in time.